This essay by Rabbi Dr. Shuky Reiss, Head of the Herzog College Tanakh Department, was first published in the Lookstein Center Journal of Jewish Educational Leadership entitled “Teaching Tanakh”, Winter 2025

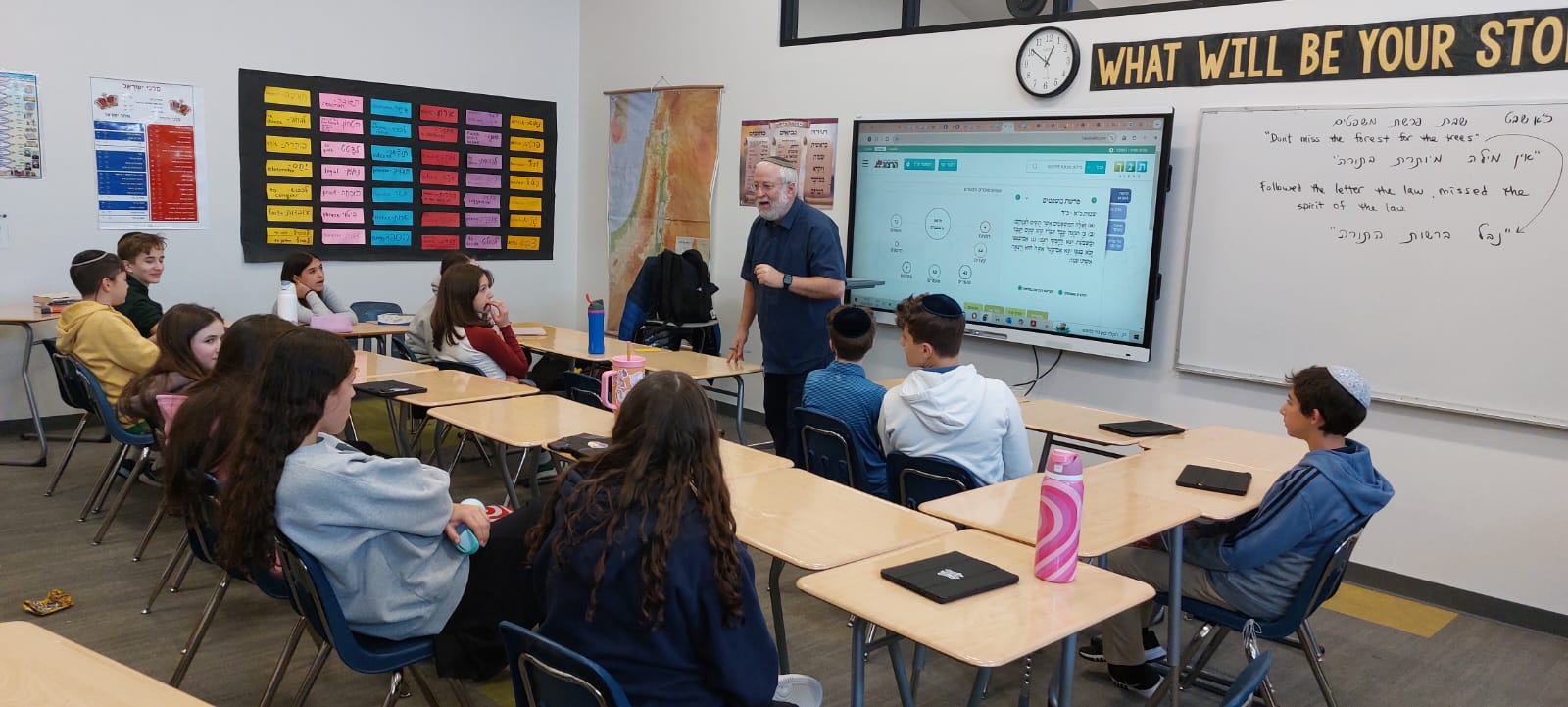

(Our photo shows Rav Shuky teaching Tanakh at SAR Academy in Riverdale, New Jersey, in February 2025.)

Introduction

The Tanakh is the story of the Jewish people. This basic component of our identity and our tradition has tremendous spiritual and educational power which, unfortunately, is often untapped. In the following essay, we aim to show how this idea of Tanakh as the grand narrative of the Jewish people can be developed into a powerful educational opportunity.

In tapping into Tanakh’s central narrative feature, we are not merely making Tanakh more interesting for our students. Since the times of Moses, the Jewish people has known that a good story does more than just pique an audience’s interest. In the words of Rabbi Sacks, “The Israelites had not yet left Egypt, and yet already Moses was telling them how to tell the story. That is the extraordinary fact. Why so? Why this obsession with storytelling? The simplest answer is that we are the story we tell about ourselves.”

With the stories we tell about ourselves shaping who we are and Tanakh being framed as the story of the Jewish people, the message is clear: Tanakh sees itself as the foundational narrative that forms our identity as Jews. In turn, our primary goal in teaching Tanakh is for all our students—from those with significant Tanakh background to those who cannot even read Hebrew yet—to utilize Tanakh’s narrative power to form their own strong, Jewish identities. We call this approach “Tanakh is Our Story,” as we endeavor to ensure that our students realize it is their story as well.

Before delving into the pedagogy of our approach, it is worthwhile to see how Tanakh presents itself as our story. Indeed, Tanakh calls out to us to see it as the grand narrative of the Jewish people. Let us take a moment to hear this call.

If one zooms out, its easy to see how Tanakh is organized as dozens of sequential smaller stories that together form one continuous narrative. We start with universal stories: Creation, Noah, Babel. The narrative moves from the universal to the particular story of Abraham’s family. As we get to Exodus, that family becomes a chosen people. As the Torah continues, we learn about the moral and spiritual purpose of those chosen people. In the desert, we learn about the early attempts to live up to that purpose. The journey continues as we turn from Torah to the Prophets. From Yehoshua’s conquering of Israel, to the chaos of Shoftim; from the building of the Davidic dynasty and the Temple, to exile and the Temple’s destruction—Tanakh gives us the highpoints and low points of the Jewish people’s never-ending attempt to build a model society.

Even when Tanakh continues with Ezra and Nehemiah, this story continues with the hopeful attempt to restart that journey again. Thus, with Tanakh, we have a sequence of successive stories that span over 3,000 years that all fit into one larger narrative. This continuous narrative, presumably, only includes a sliver of the actions and events that occurred during these periods. Nevertheless, it is impossible to ignore and incorrect to blur this timeline. The way the Tanakh was written tasks us, its readers, to not look at the individual books within it as isolated events. Rather, we are called on to see Tanakh as telling a single grand narrative that is meant to be our narrative: The story of the chosen, Jewish people’s never-ending pursuit of living up to what they were chosen to do.

Moreover, when zooming into a given book, one sees how each book tells its own story within this larger grand narrative. Indeed, within every book, we find the four elements of every story: time, place, character development, and plot. Take even the seemingly story-less Leviticus. Leviticus has a time and place: Sinai immediately after the Ten Commandments. It has developing characters: the Jewish people learning to form a holy society. And, like any good story, it has key themes: Holiness, Priesthood etc.

Thus, Tanakh presents itself as a sequence of smaller stories within a larger, grand narrative that Tanakh wants us to see our grand narrative. In turn, if we want to fully capitalize on the identity forming potential of Tanakh’s story in our classrooms, we must tap into these narrative features. In the next section, we show our pedagogical theory for how to do so.

Pedagogical Vision

This theory has two goals. Firstly, students should know the grand narrative of the Jewish people. Therefore, it’s critical that students zoom out and look at Tanakh as a whole. That means that it is necessary to familiarize them with the entirety of Tanakh’s central events and the prominent characters who stood at the center of those stories. Secondly, they should utilize that grand narrative and the different stories within it as identity-forming tools. Therefore, it is critical that we teach our students in a way that enables them to reflect on how each of Tanakh’s stories relates to them.

These two goals entail two major pivots in how we teach Tanakh. First, in looking at Tanakh as one grand narrative, our teaching should constantly point out how each story we learn figures into the larger story of Tanakh as a whole. Second, to properly utilize Tanakh’s identity-forming tools, teachers should emphasize the narrative structures of the particular story they are teaching: its character development, plot, setting. Indeed, we have all experienced a well-told story’s magical ability to get us to identify with its characters, its theme, or its conflicts. In tapping into the narrative structure of Tanakh’s stories, we enable our students to have those moments of identification with our story.

This emphasis on the narrative structures of the stories necessitates a significant shift in what we focus on in our classrooms. Indeed, we emphasize focusing on basic understanding of the text and familiarity with the biblical stories rather than intensive engagement in literary analysis or parsing through Rabbinic commentaries This is not because the latter methods of study are incorrect, but rather because the latter methods of study are better suited for advanced students who can devote large swaths of time to Tanakh study. In jumping too early to these advanced forms of study, students miss the first foundational level of Tanakh study-knowing the basic storyline. Moreover, for those with less time or less background, if they are spending all of class struggling to read a Ramban or translating a verse, they won’t get to the discussion of the themes of a story. In turn, they won’t achieve the second goal of our vision: enabling our students to connect to the themes of Tanakh and be inspired by them.

Case Study: Teaching the Ten Plagues

To see the theory in practice, let us look at how we would teach the story of the ten plagues.

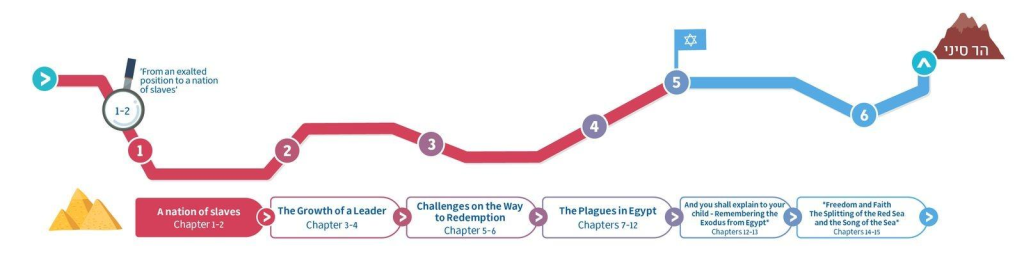

To achieve our first goal of seeing the grand narrative, an important step in our teaching is locating the plagues within the broader Exodus story. The graphic is an example of how we could achieve this goal in our classrooms. Here, the Exodus story is divided into six sections. With our students, we take a moment to zoom out. Where are we in the story? Where are we coming from and where are we going? Moreover, notice that the map does not depict the Exodus story as purely linear. This is because we want our depiction of the story to reflect the highs and lows of Exodus’ redemptive story. Indeed, even after the Jews leave Egypt, they still struggle; redemption has dips. In turn, with the second goal of identifying with the grand narrative in mind, looking at the map is a great opportunity to pause and reflect on the meaning of redemption being non-linear. We can ask our students how they can relate to the fact that sometimes in eras of prosperity, the Jews still have challenges. In reflecting on the redemptive process and placing our story within it, we have achieved our first goal: enabling our students to see the grand narrative.

As we zoom into the narrative structure of the plagues, we are now ready to focus on our second goal: student identification. We have two distinct goals in teaching the plagues themselves. Firstly, we want to make sure that our students know the plot: basic familiarity with the plagues. This can be done as a series of projects e.g., each student group presenting to the class the basic plot elements of an assigned plague (plague warnings, who the plague affected, etc.).

Once the students know the basic story, we are now ready to work on our primary goal-enabling the students to find relevance in the plague story and its themes. For this example, we would like to unlock the themes with a particular focus on character development of the Egyptians as well as the effect of the plagues on the character of the Jewish people.

In class, we would ask our students to review the warnings given to Pharaoh and the Egyptians before the plagues, as well as the story’s setting. In looking at the characters of Pharoah and the Egyptians, students would discover that the plagues weren’t just for the Jews. By utilizing the plagues to attack the Egyptian gods, and having Moses give lessons in his warnings to Pharoah, the plagues were also an attempt by God to educate the Egyptians. Indeed, one repeated message throughout the plagues is, “and the Egyptians shall know that I am God.”

With this theme of the Egyptians knowing God now on the table, we can achieve our second goal of student identification. Students can zoom out and start to think about how this value fits into their own lives. We can challenge the students to think about what role do we, as Jews, have in teaching Jewish values to the Egyptians in our days? Why is it important for everyone to know that our God is the true God, Master of All?

Notice that in teaching the plague story, we do not focus on the ways different commentaries see the plagues. Rather, we kept our eyes on the plot. (Sometimes we do utilize commentaries, but it’s always in a limited fashion.) Moreover, once the students have mastered the plot, we do not get bogged down in the literary intricacies of the relation between the different plagues. Rather, we focus on the narrative elements—the Egyptians’ character development and the themes that emerge from their development. This allows us to quickly move to the plague’s thematic meaning. Once we are already thinking about the plagues thematically, we can easily challenge our students to think about how the Biblical story affects their own contemporary stories. We simply ask our students how these themes relate to them.

Thus, in zooming out, we enable students to appreciate the bigger picture that every story we learn fits into. We enable them to see that they aren’t merely learning Exodus; they are learning part of the grand narrative of the Jewish people. In zooming into the story elements of the plagues, we enable our students to think about how this story relates to them. By focusing on the plot, the characters, and the themes that emerge from those story elements, we enable the students to recognize that our Torah is a living Torah, that has relevance to them, our students, as they write its next chapter.

To explore Rav Shuky’s approach to teaching Tanakh as “Our Story”, visit the “Tanakh Is Our Story” website or find out more about this exciting interactive curriculum here.

Special thanks to Cobi Nadel from Herzog Global for helping with translating and editing this essay.